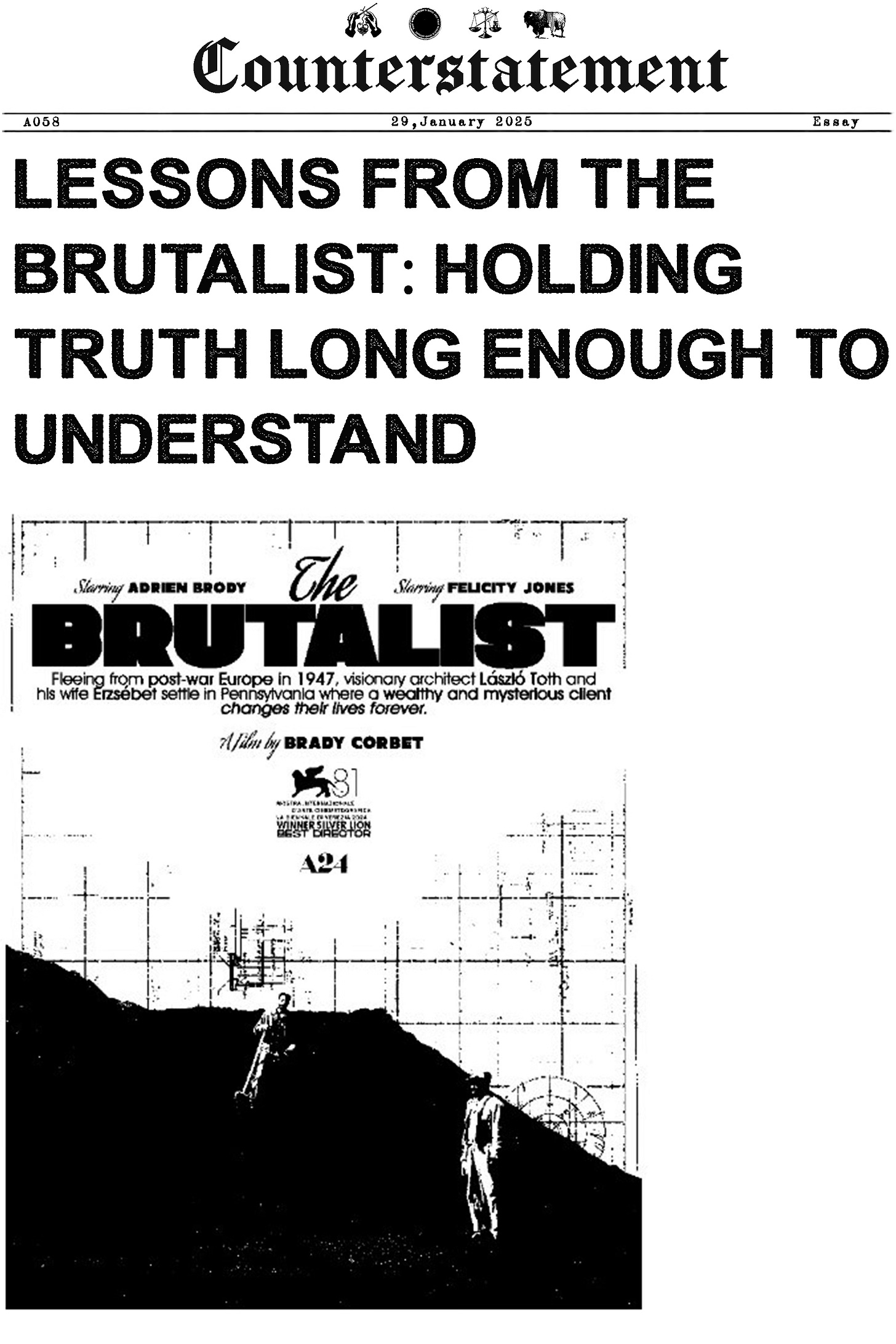

Let me make one thing clear upfront: this isn’t some deep dive into The Brutalist and its labyrinth of themes or complexities. I’m not here to decode its plot or dissect its narrative threads. Instead, this is an essay on an artistic concept, a philosophy of art that the film sparked within me. That said, if you’re the kind of person who considers even the vaguest mention of a film’s details, like the color of the curtains, an unforgivable spoiler, this is your cue to exit. I’m not revealing plot twists, but I do touch on its artistry, if even that much sends you into a spoiler panic, consider yourself warned.

Last week, I hit a rare dead zone: no words, no ideas, nothing worth writing. For someone who usually has a cluttered mental inbox of half-baked concepts screaming for attention, it was unsettling, a quiet I didn’t ask for and certainly didn’t enjoy. But then a friend dragged me to The Brutalist. The moment the film began, it was like biting into raw meat, visceral, bloody, and exactly what I needed. Suddenly, ideas were crawling all over me, and I was furiously jotting notes in the dark like some deranged scribe (yes, brightness turned down, don’t worry).

This isn’t a film critique, I’m no cinephile, and who cares anyway? I’m not here to dissect the film’s themes or explore its complexities. That’s not the point. What mattered to me was what it sparked. Often, when I experience art, I don’t go in looking to untangle its every thread or decode its every message. I’m just hoping to walk away with something, something that inspired me, that spoke to me, that rattled loose some corner of my mind I hadn’t noticed was stuck. And The Brutalist did exactly that.

One note I scribbled during the film sums it up: “It all depends on how life is presented, it can all be beautiful, depending on how you frame it. Is that the role of the artist? ” In this film the cinematography didn’t just capture stark beauty, it weaponized it. Barren workspaces, skeletal structures, and stripped-down rooms, shot and lit like they were sacred relics. The mundane, harsh realities and the raw became sublime. It’s a masterclass in what artists do best, dragging something terrible, raw, and ordinary into the spotlight, dressing it with color, composition, and light until it stands there, transformed, demanding worship.

This isn’t about romanticizing suffering, don’t mistake me for that kind of poet. It’s about wielding optimism like a weapon. And this film? It taught me that aesthetic mastery can cut through the noise, take the unbearably mundane or the unflinchingly awful, and force you to wrestle with it. It doesn’t ask for your approval, it demands your attention. Somehow, it’s almost... optimistic. The rawness doesn’t drown you, it’s dressed so beautifully, framed so perfectly, that even the ugliest truths feel survivable.

The kind of optimism I’m talking about doesn’t blunt life’s sharp edges, it hones them into a blade so exquisite you’re forced to admire the cut even as it slices. True artists, at their peak, don’t sugarcoat reality, they don’t wrap it in gauze or offer polite lies. They take the unvarnished, brutal truth and twist it into something so striking, so achingly beautiful that you can’t look away. They don’t make the unbearable easier, they make it impossible to ignore.

Color, lighting, texture, composition, sound, dialogue, all the tools of the craft are weapons of seduction, pulling you in before you even realize it. And once you’re there, mesmerized by the beauty, they make you confront the truth head-on, raw, jagged, and unrelenting. This film taught me something essential: if you want to say something so brutally honest, something the world flinches to hear, then you must make it beautiful. Wrap the truth in artistry, make it irresistible, so that even the harshest realities become impossible to turn away from. Beauty, when wielded with precision, isn’t an escape, it’s a trap. A gorgeous, deliberate, necessary trap.

This film does exactly that. It turns the harsh, the grotesque, and the utterly mundane into something worth staring at, worth feeling. A workspace morphs into a cathedral. A concrete block transforms into a shrine. And a man, average looking, at best, becomes magnetic, even mythical. It’s a reminder that beauty, when wielded with intent, doesn’t just transform, it transcends.

The film hammered this idea home with devastating beauty. Sweeping shots of mountain ranges and barren hillsides, rendered in colors so lush they felt almost edible, were juxtaposed with brutal truths, poverty, displacement, racism, addiction, assault, war. These were not incidental landscapes, they were deliberate compositions, aching with beauty and laden with meaning. And yet, the beauty didn’t soften these realities, it rendered them bearable without stripping away their weight. It was like being handed a burning coal in a silk glove, painful, yes, but you could hold onto it just long enough to understand.

This juxtaposition wasn’t just visual, it was thematic. The film’s most breathtakingly beautiful scenes, the ones that made your chest tighten and your pulse slow, were precisely where it chose to deliver its heaviest messages. These weren’t just moments to admire, they were traps, luring you in with their grandeur only to strike you with raw, unvarnished truth. In one scene, subtitles quietly displayed over a scene of endless, rolling hills, colors melting together like an Impressionist painting, only for the dialogue to cut deep, a reflection on exile, on the loneliness of being unmoored from one’s homeland and the harsh realities of pursuing one's ideals amongst people who don’t agree. It’s a paradox that hits harder because of the beauty. You’re left reeling, the message piercing you more effectively because your defenses were disarmed by the sheer magnificence of the image.

This pattern repeats consistently throughout the film, like a recurring theme. The film’s cinematography wields its brilliance like a scalpel, slicing through structures, skylines, and sunsets so vivid they sear the soul, beauty so intense it’s like staring directly into the sun: dazzling, annihilating, and leaving you blinking in the dark. But just as your retinas recover, it marches the monologue, displacement, war, scars etched deeper than time. These juxtapositions aren’t happy accidents; they’re deliberate ambushes, crafted with cruel but necessary precision to make you cradle two opposing truths at once: that the world is both breathtakingly beautiful and unforgivably brutal. A cosmic joke, really, one that leaves you laughing in discomfort and choking on its punchline.

Take the scene where László Tóth and Gordon are perched on an unfinished bridge, a skeletal monument to labor and despair. The work conditions are as brutal as the concrete around them, faces smeared in black dirt, bodies worn down by sheer effort. It’s bleak, almost suffocating, and yet the way the scene is shot makes it strangely transcendent. The color, the texture, the stark contrast between their tattered clothing and the open sky, they all collide in a composition so striking it’s impossible to look away. It doesn’t deny their suffering, it reframes it. The beauty doesn’t lie to you. It doesn’t whisper, “It’s not that bad.” Instead, it shouts, “It could get better.”

That’s the brilliance here, the beauty doesn’t dismiss the pain, it makes you feel it, but in a way you can bear. It takes the weight of their misery and adds a glimmer of hope, like a beam of sunlight through the dust. The scene is raw, the reality is harsh, but the artistry dares you to believe that maybe, just maybe, there’s a path forward. And that’s why it lingers, it forces you to wrestle with the suffering, to see it, to hold it, but also to find the spark of something more.

Would we even care about the human condition if it wasn’t wrapped in art, in story, in poetry? Would we endure the weight of existence without music, film, or stained-glass windows casting heavenly light over our darkest thoughts? Religions understood this instinctively. They embedded harsh truths about life and death into mythological grandeur, surrounding them with awe-inspiring art to draw us in and make us stay.

Religions, at their core, wielded beauty as a tool of survival. They knew the truths they carried, of mortality, suffering, and cosmic indifference, were too heavy to bear unadorned. So they cloaked them in rituals, cathedrals, and sacred texts etched with poetry so luminous it felt divine. The stained-glass windows were not just decorative, they were portals, reframing life’s brutality through kaleidoscopic light, softening the blow without denying its impact. Myths, too, served this purpose, embedding existential truths in epic tales of gods and heroes, making them both unforgettable and easier to swallow. The beauty of these creations didn’t negate the harshness of their messages, it sharpened them, much like the film does with its juxtaposition of grandeur and brutality.

This is the alchemy of art, and why beauty is essential to understanding the human condition. Like religion, art offers us a way to hold the unbearable without being consumed by it. It doesn’t erase the weight of truth, it transforms it into something we can approach, something that beckons us instead of repelling us. Just as a congregation gathers beneath the soaring arches of a cathedral to confront the mysteries of existence, we are drawn to the art that reframes suffering in a way that allows us to keep looking, to keep feeling, and to keep wrestling with it. It is the same mechanism, truth made tolerable, even magnetic, through beauty. That’s what art does at its best, it makes you bleed, makes you laugh at the absurdity of it all, and dares you to find meaning in the mess. If that’s not worth celebrating, I don’t know what is.