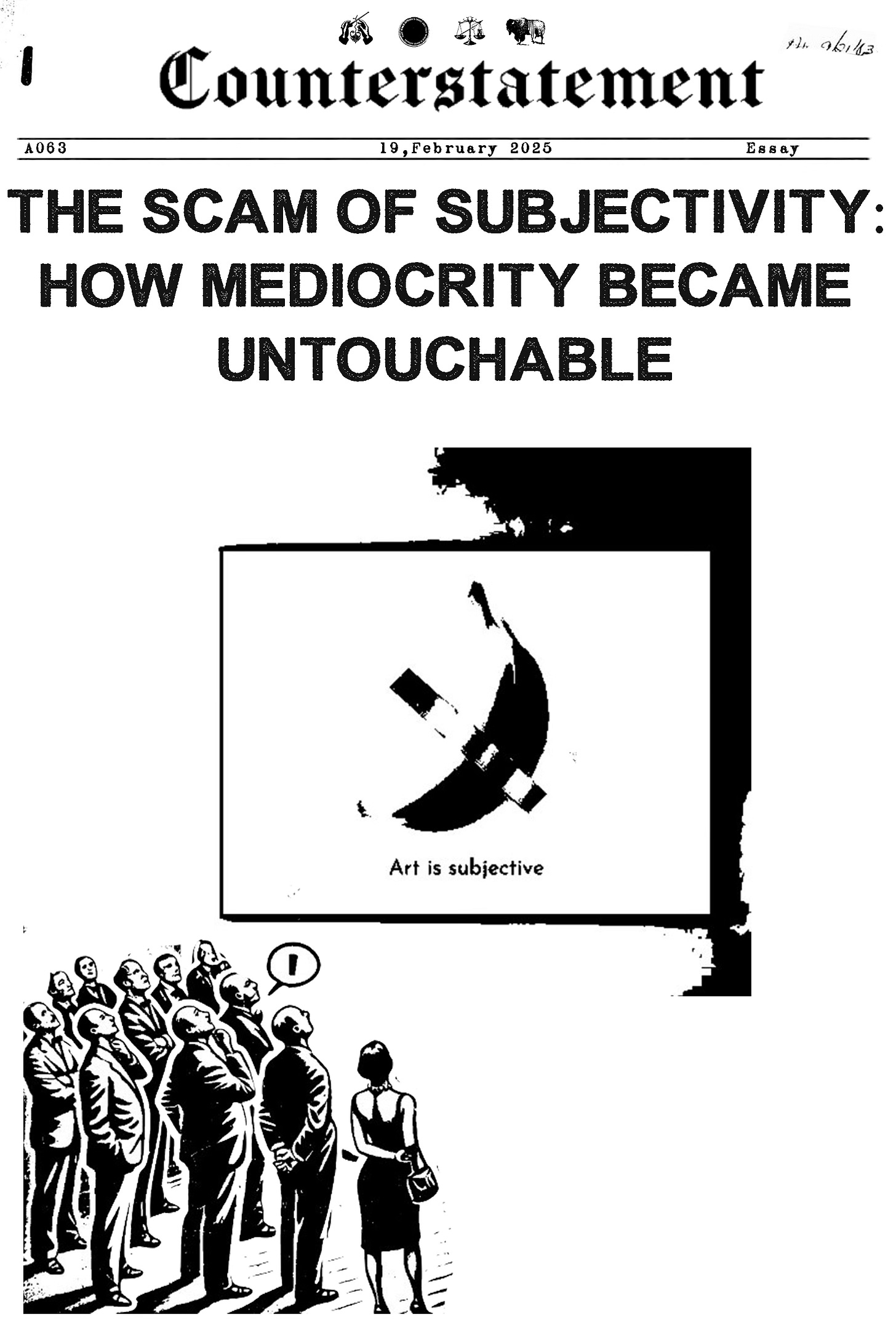

The “Art is Subjective” Cop-Out: A Shield for the Untalented and the Unwilling

There is a certain breed of person who, upon being confronted with even the mildest critique of their work, clutches their pearls, adopts the air of a persecuted visionary, and, with the sobriety of a martyr before the stake, declares: “Well, art is subjective.”

Ah yes, the rallying cry of the untalented, the battle hymn of the creatively barren, the ultimate get-out-of-jail-free card for anyone unwilling to accept that their artistic endeavor is a flaccid, lifeless husk of an idea, dressed up in the emperor’s new clothes and foisted upon an audience that, quite frankly, deserves better.

Let’s be clear: art contains subjective elements. A work of art can be personally meaningful to one person and completely insufferable to another. Some people cry at Rothko’s color fields, others see overpriced wallpaper. That’s fine. But when people wield “art is subjective” as an unassailable defense against critique, they are not making a grand philosophical statement about the fluid nature of beauty and expression. No, they are trying to shield themselves from the cold, hard truth: some art is just bad.

The Weaponization of Subjectivity

The problem with this tired defense is that it collapses the distinction between preference and quality. It pretends that all creative expression exists in a vacuum, untouched by craftsmanship, skill, historical context, or, God forbid, effort. In this delusion, a hastily scribbled doodle and a Caravaggio masterpiece are functionally equal because, well, “it’s all just opinion.” This is a lie told by people whose egos cannot withstand the weight of reality.

Imagine if we applied this logic elsewhere. Imagine a surgeon, after botching an operation, shrugging and saying, “Well, medicine is subjective.” Or a chef serving you a plate of raw chicken and smugly explaining, “Taste is a personal experience.” The absurdity would be obvious. But in the lawless wasteland of contemporary creativity, mediocrity masquerades as profundity, and questioning it is treated as some unforgivable act of cruelty.

What Makes Art "Good"?

To be clear, no one is demanding that all art follow a rigid formula, but the best creative works, be it fashion, painting, literature, or film, tend to share some common pillars:

Technical Proficiency – Whether it’s tailoring, composition, or brushwork, there is a difference between intentional rawness and amateurish sloppiness. You don’t have to like Wagner, but you cannot deny he knew how to orchestrate a symphony. Likewise, an artist who claims to “reject the rules” should probably learn them first. Otherwise, what they’re rejecting isn’t convention, it’s competence.

Intentionality – A strong artistic vision does not mean throwing paint at a canvas like a deranged chimpanzee and calling it "a statement on consumerism." Intentionality means crafting work that reflects a clear purpose, whether it's to provoke, delight, or disturb. If your work is indistinguishable from a mistake, it might just be a mistake.

Emotional or Intellectual Impact – Art should either make you feel something or think something. Ideally, both. If your creation elicits nothing but a vague sense of boredom, it has failed.

Originality & Depth – Not everything needs to be groundbreaking, but if your work is a lukewarm rehash of something better, it’s not avant-garde, it’s just redundant. There is a vast chasm between homage and uninspired mimicry, between reinterpretation and outright regurgitation. Great art builds upon what came before it, injecting new perspectives, fresh ideas, and undeniable presence. If your work is a hollow echo of something superior, then it is not a bold statement, it’s background noise.

Cultural & Timeless Relevance – Some art thrives because it speaks to a moment, others endure because they tap into something universally human. A strong piece of art, even if divisive, leaves an imprint. It sparks dialogue, lingers in the mind, and demands attention. Forgettable work, on the other hand, dissolves into the ether, leaving behind nothing but the faint, embarrassed stench of wasted effort.

The False Romance of the “Misunderstood Genius”

Of course, no conversation about bad art would be complete without addressing its most delusional defense mechanism: the misunderstood genius complex. This is the myth that any critique is simply proof that the artist is ahead of their time, a misunderstood luminary whose brilliance will only be recognized in some future utopia where people are finally smart enough to get it.

Let’s be honest, most of the time, you are not Van Gogh, and you are not Kafka, or any other artist who was dismissed in their time only to be later canonized. The difference between those artists and the mediocre creatives hiding behind their martyrdom is that the greats had substance. They had a depth and a vision that, while initially overlooked, proved too potent to be ignored forever.

Bad artists, however, are often not misunderstood, they are simply unremarkable. And in a world oversaturated with content, being unremarkable is the artistic equivalent of death.

Why This Matters

Some might argue, “Who cares? Let people make what they want!” And sure, in the grand scheme of things, another talentless hack slapping together a half-baked project and calling it “art” is hardly a threat to civilization. But the problem arises when this complacency seeps into our collective standards. When mediocrity is tolerated, it is eventually celebrated. And when it is celebrated, it becomes the new benchmark.

At some point, we have to ask: do we really want a creative culture where quality no longer matters? Where ambition is replaced by apathy, and effort is deemed unnecessary? A culture that celebrates the act of creating rather than the result?

Because if we keep accepting “art is subjective” as an impenetrable shield against criticism, then we are essentially agreeing that nothing matters. That good and bad are illusions. That skill, intention, and vision are irrelevant. And that is the kind of thinking that paves the way for a generation of lazy, uninspired hacks who confuse participation with achievement.

Final Thought: Stop Making Excuses

If you are an artist and find yourself clinging to “art is subjective” every time your work is challenged, consider the possibility that you are using it as a crutch. Instead of treating critique as an attack, treat it as a reality check. Does your work hold up under scrutiny? Does it stand on its own, or does it need the scaffolding of excuses and defensive rhetoric to remain upright?

The best artists, the ones whose work stands the test of time, aren't the ones who run from criticism. They are the ones who confront it, refine their craft, and create work so undeniable that no one needs to argue its merit.

Because when something is truly great, it doesn’t need the excuse of subjectivity to justify its existence. It simply is.